|

COMPARATIVE SPEAKERS' STRENGTH OF SCHEDULED LANGUAGES -1971, 1981, 1991 AND 2001 |

|||||||||

|

Languages

|

Persons who returned the language as their mother tongue |

|

|||||||

|

1971 |

1981 |

1991 |

2001 |

1971 |

1981 1 |

1991 3 |

2001 4 |

||

|

INDIA |

548,159,652 |

665,287,849 |

838,583,988 |

1,028,610,328 |

97.14 |

89.23 |

97.05 |

96.56 |

|

|

1 Hindi |

202,767,971 |

257,749,009 |

329,518,087 |

422,048,642 |

36.99 |

38.74 |

39.29 |

41.03 |

|

|

2 Bengali |

44,792,312 |

51,298,319 |

69,595,738 |

83,369,769 |

8.17 |

7.71 |

8.30 |

8.11 |

|

|

3 Telugu |

44,756,923 |

50,624,611 |

66,017,615 |

74,002,856 |

8.16 |

7.61 |

7.87 |

7.19 |

|

|

4 Marathi |

41,765,190 |

49,452,922 |

62,481,681 |

71,936,894 |

7.62 |

7.43 |

7.45 |

6.99 |

|

|

5 Tamil 2 |

37,690,106 |

** |

53,006,368 |

60,793,814 |

6.88 |

** |

6.32 |

5.91 |

|

|

6 Urdu |

28,620,895 |

34,941,435 |

43,406,932 |

51,536,111 |

5.22 |

5.25 |

5.18 |

5.01 |

|

|

7 Gujarati |

25,865,012 |

33,063,267 |

40,673,814 |

46,091,617 |

4.72 |

4.97 |

4.85 |

4.48 |

|

|

8 Kannada |

21,710,649 |

25,697,146 |

32,753,676 |

37,924,011 |

3.96 |

3.86 |

3.91 |

3.69 |

|

|

9 Malayalam |

21,938,760 |

25,700,705 |

30,377,176 |

33,066,392 |

4.00 |

3.86 |

3.62 |

3.21 |

|

|

10 Oriya |

19,863,198 |

23,021,528 |

28,061,313 |

33,017,446 |

3.62 |

3.46 |

3.35 |

3.21 |

|

|

11 Punjabi |

14,108,443 |

19,611,199 |

23,378,744 |

29,102,477 |

2.57 |

2.95 |

2.79 |

2.83 |

|

|

12 Assamese 2 |

8,959,558 |

** |

13,079,696 |

13,168,484 |

1.63 |

** |

1.56 |

1.28 |

|

|

13 Maithili @ |

6,130,026 |

7,522,265 |

7,766,921 |

12,179,122 |

1.12 |

1.13 |

0.93 |

1.18 |

|

|

14 Santali |

3,786,899 |

4,332,511 |

5,216,325 |

6,469,600 |

0.69 |

0.65 |

0.62 |

0.63 |

|

|

15 Kashmiri |

2,495,487 |

3,176,975 |

# |

5,527,698 |

0.46 |

0.48 |

# |

0.54 |

|

|

16 Nepali |

1,419,835 |

1,360,636 |

2,076,645 |

2,871,749 |

0.26 |

0.20 |

0.25 |

0.28 |

|

|

17 Sindhi |

1,676,875 |

2,044,389 |

2,122,848 |

2,535,485 |

0.31 |

0.31 |

0.25 |

0.25 |

|

|

18 Konkani |

1,508,432 |

1,570,108 |

1,760,607 |

2,489,015 |

0.28 |

0.24 |

0.21 |

0.24 |

|

|

19 Dogri |

1,299,143 |

1,530,616 |

# |

2,282,589 |

0.24 |

0.23 |

# |

0.22 |

|

|

20 Manipuri $ |

791,714 |

901,407 |

1,270,216 |

1,466,705 |

0.14 |

0.14 |

0.15 |

0.14 |

|

|

21 Bodo 2 |

556,576 |

** |

1,221,881 |

1,350,478 |

0.10 |

** |

0.15 |

0.13 |

|

|

22 Sanskrit |

2,212 |

6,106 |

49,736 |

14,135 |

N |

N |

0.01 |

N |

|

|

Source: Census of India, 2001, Government of India |

|||||||||

Indian literary history shows that people used to switch between Pali and Sanskrit, Tamil and Sanskrit, and Ardhmagadhi and Sanskrit with ease. During the Mogul period, there were many scholars who had mastered both Sanskrit and Persian/Arabic. Tulsidas, Vidyapati, and authors of Apabhramsa of the North, and the Azhwars and Nayanmars of the South emphasized the importance of the language styles spoken by the ordinary people, even as they used the language of high literature. Indian classical drama used dialects and 'standard' languages. Writers used Magadhi, Shaurseni, Prakrit, and Apabhramsa, even as they excelled in the use of Sanskrit. The pattern of language use seemed to be flexible depending upon what roles the individual was playing.

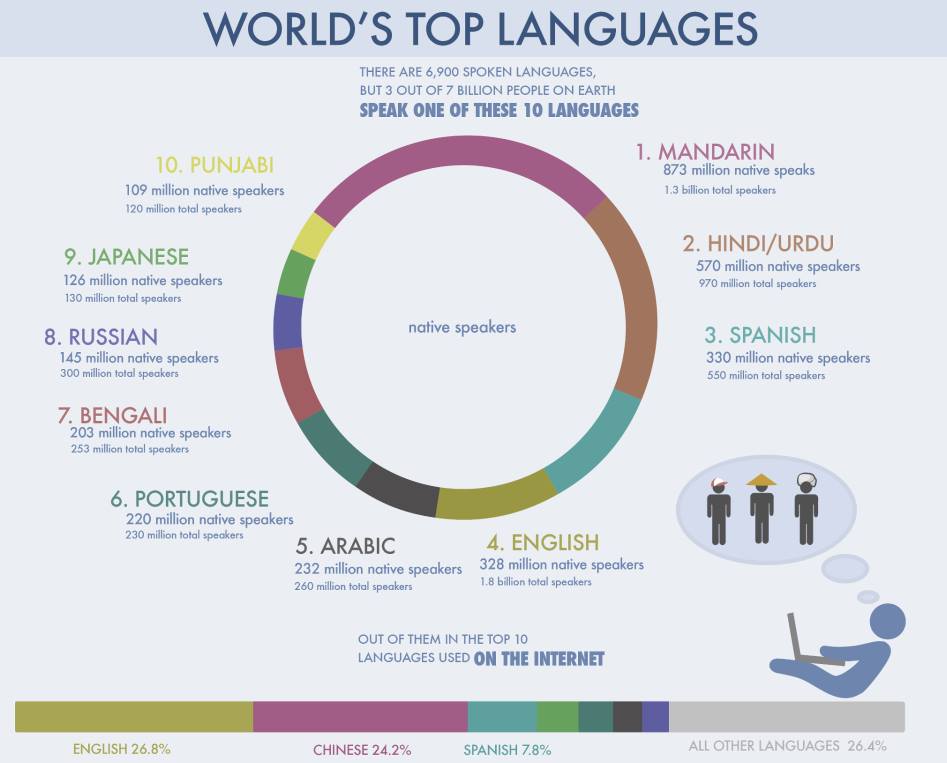

The above explanations are justified by the census reports of India. The number of bilinguals is on the increase from Census to Census. Their national average is:

1961- 9.70%; 1971- 13.04%; 1981- 13.34%; 1991- 19.44%.

Some important results, in the case of the major languages, emerging from the 1991 Census are as follows:

18.72% are bilinguals and 7.22% are trilinguals and the bilinguals among minor languages are 38.14% and the trilinguals are 8.28%.

Significantly, among major language speakers, the spread of bilingualism in English is more (than in Hindi)

8% as second language, 3.15% as third language whereas the same in Hindi is 6.15% and 2.16%.

The Language Policy of India relating to the use of languages in administration, education, judiciary, legislature, mass communication, etc., is strikingly pluralistic in its scope. It is both language-development oriented and language-survival oriented. As a policy it is intended to encourage citizens to use their mother tongue in certain delineated levels and domains through some gradual processes, but the stated goal of the policy is to help all languages to develop into fit vehicles of communication at their designated areas of use, irrespective of their nature or status like major, minor, or tribal languages. (reference [1] B. Mallikarjun ).

The Constitution of India listed fourteen languages (Assamese, Bengali, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Kashmiri, Malayalam, Marathi, Oriya, Punjabi, Sanskrit, Tamil, Telugu, and Urdu) into its Eighth Schedule in 1950. Since then, this has been expanded thrice, once to include Sindhi, at another to include Konkani, Manipuri and Nepali, and just this month to include Bodo, Santhali, Maithili and Dogri. The 100th Constitution Amendment which added the latter four languages into the Eighth Schedule was supported by all the 338 members present in the Parliament. It has been stated that claims of 33 more languages for inclusion are under consideration. This list is open-ended and has become a tool to bargain and gain benefits for the languages. Once a language gets into this club, its very nomenclature and status will change, and it will be called Modern Indian Language (MIL), Scheduled Language (SL), etc.

In addition it should be noted that languages are not only classified under schedule or non schedule languages, but rather they have been further grouped at the level of mother tongues into "languages." Though 122 languages are arrived at by the Census Office, many of these languages are not independent and individual entities as such. Within these, there are many mother tongues/languages/dialects. The group of "languages" is formed by clustering the populations of many mother tongues under an umbrella called "language." For example, Hindi is a cluster of more than 49 mother tongues, which include Awadhi, Banjari, Bhojpuri, Braj Bhasha, Bundelkhandi, Chambeali, Chattisgarhi, Garhwali, Haryanvi, Kangri, Kulvi, Labani, Magahi, Maithili, Marwari, Mewari, Pahari, Rajasthani, Sadri, Sugali, etc.

It is worth mentioning the encouraging reports by UNESCO that has appreciated India’s stand " on maintaining linguistic diversity” ... (when) about half of the approximately 6000 languages spoken in the world are under threat, seriously endangered or dying," it does appreciate that "India has maintained its extensive and well-catalogued linguistic diversity".

We have already mentioned that this linguistic diversity reflects those related to ethnicity, religion, social identity, rural/urban, literate/illiterate, etc. Surprisingly, these often constitute the strength of a multi-facet society like India. The downside of this diversity is that it has often given rise to bitter differences. Yet, today, its role as a threat and challenge to this vibrant nation pales before that of the Digital Divide.

It is interesting to note that though the Information Technology boom has brought a revolution top India and Indian computer wizards are making waves in the Silicon Valley, yet the Digital Divide continues to plague the nation. The pace at which Indian society is trying to absorb these technologies through its organs such as language has added one more divide to those already in existence - the "digital divide" resulting in the disparity in access to information and to the means of communication in 21st Century India.

Computer penetration in India is estimated to be 7.5 per 1000 people but at the same time the internet is able to reach only about one percent of the total population of the country. The early Government of India information technology boom outreach initiatives, alas but understandably, mostly used English as medium of mass penetration for computer literacy. However, to bridge this divide, the Government has taken a series of initiatives in developing computer applications in Indian languages. It is worth mentioning the initiatives by the Ministry of Communication and Information Technology in the form of The Technology Development for Indian Languages (TDIL). TDIL has been mandated to bridge the digital divide by developing IT tools in local languages in India.

Since 1991, TDIL reference [2] has sponsored research in developing Indian language computing resources, processing systems, tools and translation support systems and localization of software for Indian languages. The other key initiatives have come in from the development of Human-Machine Interface Systems and web centric applications. TDIL operates on a distributed innovation model through collaborations with 13 resource centers across India. Some of the notable milestones have come through CDAC reference [3], a collaborative partner of TDIL in the form of GIST (Graphics and Intelligence-based Script) that has brought diverse users to employ local language IT tools. Applications have ranged from desktop publishing to sub-titles in TV broadcasts in various Indian languages. A Local Language word processor, ‘LEAP' has brought desktop publishing to a large segment of population in a language they can communicate in naturally.

The initiatives of CDAC in language technology initiatives are worth a mention. They are summed up as follows. [4]

Translation Support System: A software for translation from English to Hindi based on the Angla Bharati approach of IIT, Kanpur Paninian framework fused with modern Artificial Intelligence Techniques Karak Theory used in choosing right prasarg in target text.

GyanNidhi: 1 Million Pages Multilingual Parallel Corpus in English and 12 Indian languages. Text in UNICODE format useful for applications such as improving translation systems, translation memory, spell checkers, Dictionaries, statistical text analyzer, language related research, writing style analysis and morphological analyzer.

The National Book Trust India, the Sahitya Akademi, and the Publication Division are the major contributors of texts.

Dware Dware Gyan Sampada - Mobile Digital Library: Internet Enabled Mobile Digital library brought to the common citizen for spreading literacy.

Chitraksharika: Optical Character Recognition for Devanagari Script, an efficient way to convert optically scanned images of printed materials into computer processable data files

Lekhika: Platform Independent Word Processor (Linux, Solaris, Windows, etc.) with multilingual document support.

On-Line Hindi Vishwakosh: Collection of approximately 12, 000 topics.

On Line IT Terminology: Information Technology Terminology in Hindi on Internet in Public domain.

Swarnakriti: A Unicode Based Word Processor with integrated OCRs & TTS

Also, it is worth to mention the work and initiative of Central Institute of Indian languages reference[5], Mysore that has delivered unparallel results in promoting translation and language related activities in India specially through its online network Anukriti.net that serves as resource and reference center on literature and translation in Hindi, Bengali, Tamil, Telugu and all other Scheduled and Non Scheduled Indian languages under vision and guidance of well known scholar and writer Dr. Uday Narayan Singh Reference [7]

In addition, many private players including Indian and multinational giants like Microsoft, IBM, Infosys, Wipro, TCS, Reliance, Airtel, Vodafone etc. are developing software and applications in Indian languages. Needless to say, a major search engine like Google has already started offering search possibilities in Bengali, Hindi, Marathi, Tamil and Telugu, and there are a series of other major players eyeing Indian localization markets.

CAT TOOLS

Machine Translation in India is relatively young. The earliest efforts date from the late 80s and early 90s. Prominent among these are the projects at IIT Kanpur, the University of Hyderabad, NCST Mumbai and CDAC Pune. The Technology Development in Indian Languages (TDIL), an initiative of the Department of IT, the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology (Government of India), has been instrumental in funding these projects. Since the mid and late 90’s, a few more projects have been initiated—at IIT (Bombay), IIT (Hyderabad), AU-KBC Centre (Chennai) and the Jadavpur University (Kolkata).

Anglabharat (and Anubharati): Anglabharati deals with machine translation from English to Indian languages, primarily Hindi, using a rule-based transfer approach. The primary strategy for handling ambiguity/complexity is post-editing—in case of ambiguity; the system retains all possible ambiguous constructs, and the user has to select the correct choices using a post-editing window to get the correct translation.

Anusaaraka: The focus in Anusaaraka is not mainly on machine translation, but on Language Access between Indian languages. Using principles of Paninian Grammar (PG), and exploiting the close similarity of Indian languages, an Anusaaraka essentially maps local word groups between the source and target languages. Where there are differences between the languages, the system introduces extra notation to preserve the information of the source language. Thus, the user needs some training to understand the output of the system.

MaTra: MaTra is a Human-Assisted translation project for English to Indian languages, currently Hindi, essentially based on a transfer approach using a frame-like structured representation. The focus is on the innovative use of man-machine synergy—the user can visually inspect the analysis of the system, and provide disambiguation information using an intuitive GUI, allowing the system to produce a single correct translation. The system uses rule-bases and heuristics to resolve ambiguities to the extent possible – for example, a rule-base is used to map English prepositions into Hindi postpositions. The system can work in a fully automatic mode and produce rough translations for end users, but is primarily meant for translators, editors and content providers.

MANTRA: MANTRA translates the English text into Hindi in a specified domain of Personal Administration, specifically Gazette Notifications, Office Orders, Office Memorandums and Circulars. The utility of MANTRA has to be viewed in the context of the Indian environment, its socio-economic and demographic conditions, its historical background and above all the transitory phase India is passing through presently. Translating from one language to another, particularly of a different family, covers a very broad spectrum. The strategy adopted here is - NOT WORD-TO-WORD... NOT RULE TO RULE.... but a LEXICAL TREE-TO-LEXICAL TREE. MANTRA uses the Lexicalized Tree Adjoining Grammar (LTAG) formalism to represent the English as well as the Hindi grammar. The MANTRA [Footnote 7] Technology is being expanded to translate English texts into other Indian languages such as Gujarati, Bengali, and Telugu. The accuracy rate of translation in these languages is considerably high. Besides, it is also being expanded to translate Hindi text into English in the specified domain of personnel administration, as well as other domains like Banking, Transportation and Agriculture.The CS Department at the University of Hyderabad has worked on an English-Kannada MT system, using the Universal Clause Structure Grammar (UCSG) formalism, also invented there. This is essentially a transfer-based approach, and has been applied to the domain of government circulars, and is funded by the Karnataka government.

The Universal Networking Language (UNL) is an international project of the United Nations University, with an aim to create an Interlingua for all major human languages. IIT Bombay is the Indian participant in UNL, and is working on MT systems between English, Hindi and Marathi using the UNL formalism. This essentially uses an interlingual approach—the source language is converted into UNL using an ‘enconverter’, and then converted into the target language using a ‘deconverter’.

The Anna University KB Chandrasekhar Research Centre at Chennai was established recently, and is active in the area of Tamil NLP. A Tamil-Hindi language accessor has been built using the Anusaaraka formalism described above.

English-Hindi MAT for news sentences: The Jadavpur University at Kolkata has recently worked on a rule-based English-Hindi MAT for news sentences using the transfer approach.

English-Hindi Statistical MT: The IBM India Research Lab at New Delhi has recently initiated work on statistical MT between English and Indian languages, building on IBM’s existing work on statistical MT.

BhashaIndia: Microsoft India, has taken the initiative to empower Indic language computing and localization through Unicode. It is also noteworthy that Microsoft has also taken the lead by launching Windows XP enabled in local languages in the year 2005.

TRANSLATION AND LOCALIZATION MARKET

With the IT enabled Services sector poised to grow rapidly world-wide over the next few years, the Indian ITeS industry is taking rapid steps to take advantage of this opportunity. The Nasscom-Deloitte study on Indian IT Industry: Impacting the Economy and Society says the IT/ITES industry's contribution to the country's GDP has increased to a share of 5.2 per cent in 2007, as against 1.2 per cent in 1998.

And with a growth of 27 per cent in 2007, in 2008, the Indian ITES market is set to cross US$ 25.43 billion. Already, twenty-nine India-based companies have recently been listed among the best 100 IT service providers.

The below mentioned table shows the projection of revenues (worldwide) of several thousand companies active in the translation and localization related business. The calculation includes many freelancers, and an approximation of the revenue generated by international and ethnic marketing agencies, boutiques, system integrators, consultants, printers, and other service providers who facilitate translation and localization.

|

Region |

% of Total Market |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

|

U.S. |

42 % |

3,696 |

3,973 |

4,271 |

4,592 |

4,936 |

5,306 |

|

Europe |

41 % |

3,608 |

3,879 |

4,169 |

4,482 |

4,818 |

5,180 |

|

Asia |

12 % |

1,056 |

1,135 |

1,220 |

1,312 |

1,410 |

1,516 |

|

ROW |

5 % |

440 |

473 |

508 |

547 |

588 |

632 |

|

Totals |

N/A |

8,800 |

9,460 |

10,168 |

10,933 |

11,752 |

12,634 |

|

Language Services Revenues, in Millions of U.S. dollars Source: Common Sense Advisory, Inc. |

|||||||

Based on the reports of NASSCOM that India is sharing 5.2% of the ITES market, and according to the growth pattern depicted by Common Sense Advisory if we take India's share as 5% of the world market, currently language market size in Indian languages may be taken at approx. value of $ 500 millions which may be summed as follows, in terms of activities.

|

Break up of opportunities in various sectors of IL |

|||

|

S. No. |

Sector |

%age |

Revenue in $ Millions |

|

1 |

Publication |

20 |

100 |

|

2 |

DTP |

10 |

50 |

|

3 |

Content Creation |

20 |

100 |

|

4 |

Design |

05 |

25 |

|

5 |

Translation |

20 |

100 |

|

6 |

Repurposing |

10 |

50 |

|

7 |

IT Localization |

15 |

75 |

|

|

Total |

100 |

500 |

|

Source: Independent estimate from various sources reference [8] |

|||

The unique cultural diversity of the Language and Translation Industry of India thus provides rich prospects for mutually enriching collaborations across the globe. Accustomed to economize as a philosophy of life, the Indian translation industry preserves age old humanistic Asian values in an age of cut throat competition, thus bringing a two-fold benefit in an era of soaring prices and plummeting human relations.

Even with all these valiant endeavors, a lot still remains to be done by individuals and companies, as well as by the government, to promote this nascent industry and incorporate the required changes, to adapt and upgrade skills and to use new technologies but the baseline is set, and I am sure the existing synergy will translate into great opportunities for those who looks towards India as potential investment destination.

Notes and references

[1] B. Mallikarjun is well known scholar and actively involved in corpora development activities of CIIL and writes a language related articles and research papers for www.languageinindia.com and www.anukriti.net

[2] The Technology Development for Indian Languages (TDIL) is the initiative of the Ministry of Communication and Information Technology. TDIL has been mandated to bridge the digital divide by developing IT tools in local languages in India.

[3] Centre for Development of Advanced Computing (CDAC) is government of India run organization involved in research and development of computers, known of development of super computers.

[4] Courtesy: Mr. V.N. Shukla, Director Special Applications, CDAC, Noida

[5] The Central Institute of Indian Languages, Mysore, (CIIL) was set up by the Government of India in July 1969. It is a large institute with seven regional centers spread all over India, and is engaged in research and training in Indian languages other than English and Hindi. It helps to evolve and implement India’s language policy and coordinate the development of Indian languages.

[6] Dr. Uday Narayan Singh was the Director of Central Institute of Indian Languages and he was also member to National Translation Mission

[7] The Mantra project is considered one of the most innovative projects on Machine Translation, initiated and developed by Dr. Hemant Darbari, the computer scientist from C-DAC Pune in 1998. For this innovation Dr. Darbari received "The Computerworld Smithsonian Award Medal" on April 12th, 1999 from Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC This work is also a part of "The 1999 Innovation Collection" at National Museum of American History, Washington DC, USA

[8] Writers Note: The information and data, presented above, may not be taken as final in itself. Rather, it is given by way of indication to serve as support for a few of my personal views and the analysis that I intend to present to depict the overall picture of the Indian Translation Industry.